29. December 2023 | Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Younger and less satisfied? Young workers’ life satisfaction during the Covid-19 pandemic in Germany

In Germany, as in many other countries, economic activity significantly declined during the Covid-19 pandemic. For many people, the economic consequences following the pandemic entailed a substantial financial and mental burden.

Thanks to the so-called short-time work allowance scheme in Germany, permanent job loss occurred only on a limited scale. Especially at the beginning of the pandemic, the short-time work allowance was widely used in Germany to avoid the layoff of workers that employers could (temporarily) not keep busy.

Young people run a comparably high risk of being hit hard by the crisis, particularly with regard to their employment and income. Compared to more established workers, young adults have less work experience and often face higher job insecurity, not least as they are more often employed on a fixed-term basis. For the first year of the Covid-19 crisis, studies not only show a moderate rise in youth unemployment in Germany but also reveal that younger workers stay unemployed for a longer duration (see for instance Dietrich et al. 2021). These higher unemployment risks often go hand-in-hand with economic risks, such as earnings losses and income insecurity.

Beyond economic consequences, this study also accounts for pandemic-specific influences on well-being by considering Covid-19 incidence rates at the federal state level. The incidence rate may be closely linked to life satisfaction, as it is a suitable proxy indicator for individual risk of infection as well as for the prevalence of state measures, such as personal contact restrictions and the closures of shops, pubs, and theatres that go along with higher incidence rates.

Previous research points to the psychological costs of the pandemic for the population, which may be driven by individuals’ loss of socioeconomic resources during the pandemic. A 2021 study by Ursina Kuhn and others about Switzerland, for example, shows that the Covid-19 crisis reduced subjective well-being of younger adults, particularly of those aged 18 to 25 and that the deterioration of their labour market prospects may have contributed to the reduction in well-being.

The report uses data from the Institute for Employment Research’s (IAB) HOPP study (see infobox “Data and Measures”) to explore the question as to what extent the rising job and income insecurity affected the subjective well-being of German employees and their households. In this context, taking a closer look at the age group-related differences in the development of objective indicators such as short-time work and household income, as well as at their relation to life satisfaction is particularly important. This study distinguishes between three age groups: 18- to 25-year-olds, 26- to 35-year-olds, and those aged 36 or older. It focuses on the period from May 2020, the end of the first lockdown, to February 2021, after the first four months of the second lockdown, which in Germany started in November 2020 and ended in April 2021.

Lowest receipt of short-time work allowance among the youngest age group

The so-called short-time work allowance helped German firms to avoid layoffs during the Covid-19-crisis (as well as during earlier crises) for a limited period of economic turmoil. While employers apply for this measure at the Federal Employment Agency, the agency pays the allowance to employees to substitute (part of) their foregone income, when they temporarily stop working or reduce working hours. Once overall economic conditions improve, employers are thus able to reactivate their personnel easily and to start their business without having to recruit new staff.

While the overall impact of the measure is positive, since it helps to avoid layoffs, receiving short-time work allowance might nevertheless be associated with lower life satisfaction as —after all—it implies a difficult economic situation of the employer. Receiving the allowance not only entails lower income but also an increase in job insecurity as, despite relying on the allowance, the employer will eventually have to release employees or even terminate its business.

However, workers who do not receive short-time work allowance are not necessarily better off. A lower incidence of short-time work in a particular group of workers could indicate a more vulnerable labour market position of these workers as they might work in non-eligible jobs (e.g. in marginal employment).

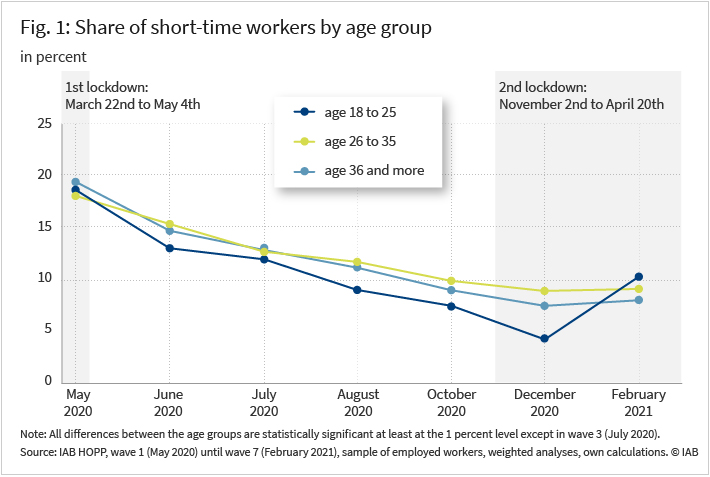

Younger employees receive short-time work allowance less often than employees in the two older age groups (see Figure 1). However, the reasons for these age-related differences are unclear. On the one hand, younger workers may have been more likely to work for employers less affected by the pandemic, or employers may have often considered younger workers to be more essential than older colleagues.

On the other hand, the lower incidence of short-time work among younger workers could indicate that they have more vulnerable labour market positions. In fact, Markus Grabka and his colleagues reported in 2020 that workers in marginal employment suffered more from the pandemic. They also show that the share of those under 25 years of age in marginal employment (so-called “Minijobs”) was substantially higher than in regular employment. Moreover, in the first wave of the survey, younger workers reported far more often that they already lost their employment due to the Covid-19 crisis: 6.4 percent of those between 18 and 25 reported loss of a Minijob (versus 2.2 % of those between 26 and 35 and 1.5 % of the 36- to 65-year-olds), while 3.9 percent lost regular employment (versus 3.4 % and 1.3 %) and 1.4 percent self-employment (versus 1.7 % and 1.7 % respectively).

Higher loss of household income for younger people

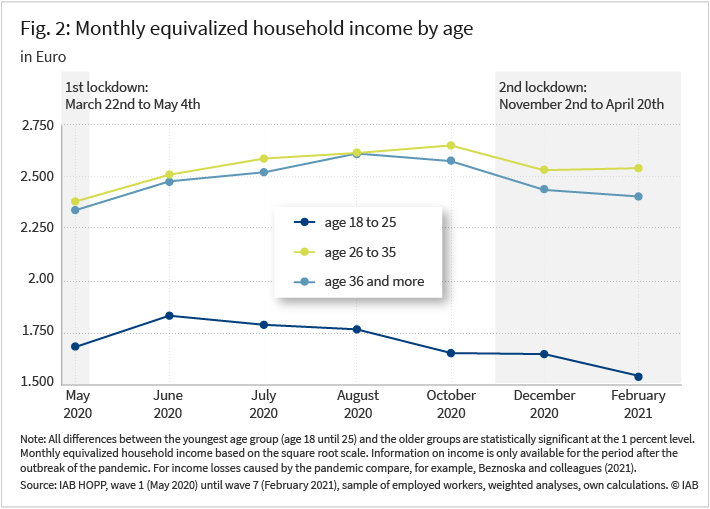

Accordingly, equivalized household income (for details please refer to the infobox “Data and measures”) also developed more favourably for the two older age groups throughout the pandemic than for those aged 18 to 25 (see Figure 2).

While household income of the older age groups increased over the summer of 2020 and only decreased with the second lockdown in December 2020, the younger age group’s income — while being at a considerably lower level — increased for a short period between May and June 2020 and displayed a negative development for the remainder of our observation period. Thus, the income gap between the age groups widened during the pandemic, with younger people experiencing higher losses and, thus, lower financial security.

Decline in life satisfaction for all age groups

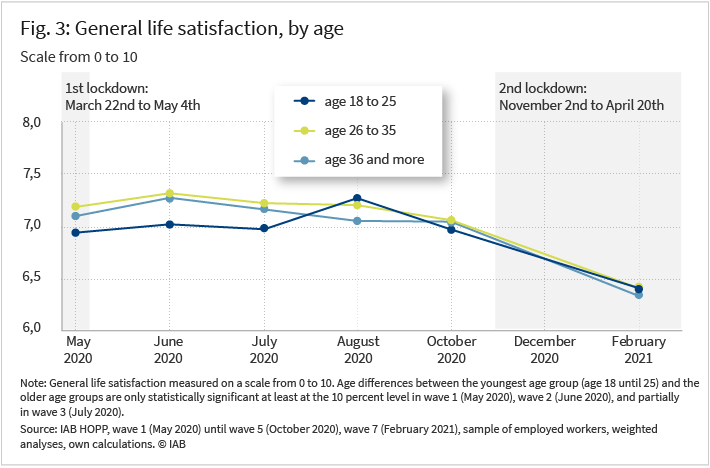

Does a greater loss of socioeconomic resources also translate into a larger drop in the life satisfaction of the young? At first sight, this does not seem to be the case. In contrast to the trend in household income, general life satisfaction—while basically going down—developed almost parallel for all age groups (see Figure 3). If anything, the small age gap at the beginning of the observation period closes because the youngest age group catches up with the two older groups over time.

However, the fact that the lowest level of life satisfaction is observed for the youngest age group at the beginning of the pandemic is surprising insofar as most approaches in the literature argue that life satisfaction decreases with age —at least until around the age of 40 to 50. The unexpected age gap in life satisfaction may be driven by age-specific differences in socioeconomic characteristics, which may cause life satisfaction of younger and older workers to reach different levels.

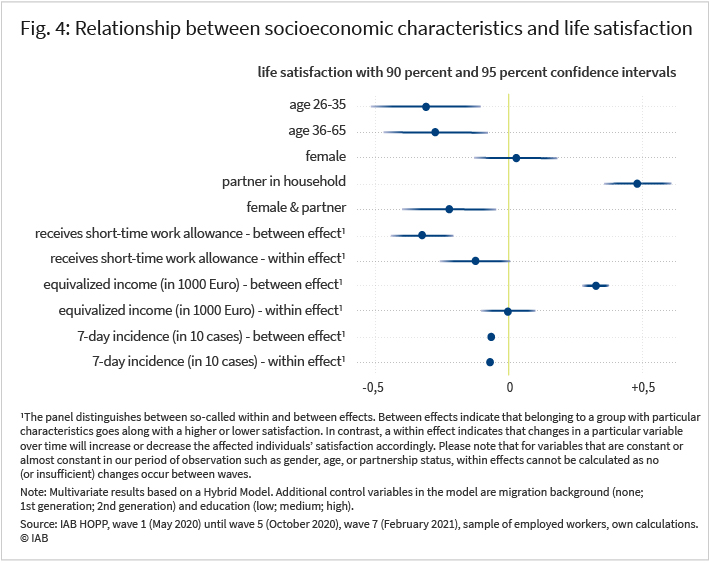

To take a closer look at the association between socioeconomic resources and life satisfaction, in this study we use a regression model including age, receipt of short-time work allowance, household income, Covid-19 incidence rates, and further relevant factors simultaneously as possible determinants of life satisfaction. While the raw regression (without including these socioeconomic characteristics) confirms that the 18- to 25-year-olds are less satisfied with their life during the observation period, the relationship between age and life satisfaction is reversed, when additional worker characteristics are included (see Figure 4). This means that if workers in the three age groups are all equal with regard to the control variables included in the model (e.g. if they had the same likelihood to live with a partner or have the same average household income), the younger workers’ life satisfaction would be higher than that of older workers. Consequentially, younger workers are less satisfied than older ones mainly due to the fact that they differ with respect to individual characteristics, which are distributed unequally between age groups and are connected to life satisfaction.

Lower life satisfaction among recipients of short-time work allowance

With respect to the socioeconomic characteristics, the results show a statistically significant positive relationship between life satisfaction and income as well as a negative relationship between life satisfaction and receiving short-time work allowance when focusing on differences between worker groups: Workers who were wealthier or did not receive short-time work allowance at any particular point in time were more satisfied with life. In addition, our statistical models allow to distinguish effects between worker groups from what is called within effects, i.e. changes in life satisfaction due to changes in worker characteristic of one and the same individual over time (between the panel waves). For example, if a person does not receive short-time work allowance in the first wave but does so in the second, and if at the same time his or her life satisfaction is reduced, this will result in a negative within effect.

If a differentiation is made between these two types of effects, it becomes obvious that—while there is a statistically significant and positive general (between) effect of income on life satisfaction—changes in income within worker groups are not significantly related to changes in life satisfaction.

In contrast, not only are those receiving short-time work allowance less satisfied with their life in general but starting to receive the allowance additionally lowers life satisfaction. Thus, even though the existence of the short-time work allowance is considered positive from an overall perspective, workers’ experience of financial and employment insecurity seems to dominate their individual judgements and satisfaction.

In contrast, it appears that living with a partner had a particularly high importance for life satisfaction during the pandemic, especially for men. Since younger and older respondents differ substantially with regard to their likelihood of living with a partner (74 % of the oldest age group, 68 % of the intermediate age group, and only 22 % of the youngest age group lived with a partner), differences in partnership status are particularly important when considering the age gap in life satisfaction.

Moreover, incidence rates, which reflect individual infection risks as well as restrictions going along with high incidence rates, seem to be an important driver of life satisfaction both between and within worker groups: Worker groups that face high incidence rates are on average less satisfied with life than workers who face low incidence rates. In addition to this, increases in incidence rates experienced by one and the same individual on average translate into lower life satisfaction.

Conclusion

Compared to older workers, young adults were more likely to have experienced adverse effects on their employment situation. They were less likely to receive short-time work allowance and, beyond the fact that young workers’ income was already considerably lower than that of older workers in the first place, the development of young adults’ income was also less favourable after the first lockdown.

While the life satisfaction of younger workers is lower than that of older workers during our observation period, when controlling for socioeconomic determinants of life satisfaction, this finding is reversed. That means if young workers had the same characteristics as older workers, e.g. the same income or likelihood of living with a partner, life satisfaction of the young would actually exceed that of older workers. In particular, partnership status and incidence rates seem to exceed the relevance of economic influences for life satisfaction.

One can conclude that, while younger adults were more vulnerable to adverse economic influences of the Covid-19 pandemic, the relevance of these economic influences for their life satisfaction seems to be limited—at least during the early phase of the pandemic. What seems to have lowered life satisfaction during the pandemic are (rising) Covid-19 incidence rates and living as a single. Particularly the lower likelihood of younger individuals to live with a partner might have contributed to their lower life satisfaction throughout the pandemic.

Data and Methods

This report is part of the “COVID-19 youth economic activity and health monitor” (YEAH), a co-operation project between the University College of London’s (UCL) Centre for Learning and Life Chances in Knowledge Economies and Societies (LLAKES), Statistics Canada, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) and the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). The project was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), grant number ES/V01577X/1.

For our analyses, we use data of the High-Frequency Online Personal Panel “Life and Work Situations in Times of Corona” (IAB-HOPP). This online survey provides new data to explore the implications of the Covid-19 pandemic on socioeconomic conditions, health, and the employment situation of the working-age population in Germany.

The dataset consists of a random sample of persons that was drawn from the Integrated Employment Biographies (IEB) of the IAB. The IEB includes administrative records of the Federal Employment Agency in Germany covering most persons in dependent employment (but excluding civil servants (Beamte) and the self-employed).

The data cover information on episodes of employment that is subject to social security contributions, of marginal part-time employment, of episodes of receiving unemployment benefits or basic income support, of participation in labour market programs and of registration as a jobseeker. The sample of the survey is limited to persons aged 18 or older on 1 May 2020 with at least one record within the IEB database of the year 2018. Haas and his colleagues (2021) provide a more detailed description of the dataset.

Our analyses rely on data from the first seven survey waves conducted between May 2020 and March 2021. In addition to descriptive analyses, we provide effect plots from a multivariate Hybrid Model.

In our analyses, we use a so-called equivalized household income to make the income of households of different size comparable. To calculate equivalized income, the household’s total income is divided by a weighted household size, which for multi-person households is smaller than the actual household size. Approaches for calculating this weighted household size (e.g. the well-known OECD equivalence scale) typically weight household members of different age differently to reflect the differing needs of adults, youth, and smaller children. As our data do not include detailed information on the age structure of household members, we equivalized household income using the square root scale approach, which divides household income by the square root of the number of people living in the household.

In brief

- Younger adults were more vulnerable to adverse influences of the Covid-19 pandemic on employment and household income than more established workers.

- However, the relevance of these economic influences for their life satisfaction seems to be limited, at least during the early phase of the pandemic.

- What seems to have lowered life satisfaction are Covid-19 incidence rates and being single. Particularly, the lower likelihood of younger individuals to live with a partner might have contributed to their lower life satisfaction throughout the pandemic.

Literature

Data and Methods

This report is part of the “COVID-19 youth economic activity and health monitor” (YEAH), a co-operation project between the University College of London’s (UCL) Centre for Learning and Life Chances in Knowledge Economies and Societies (LLAKES), Statistics Canada, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) and the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). The project was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), grant number ES/V01577X/1.

For our analyses, we use data of the High-Frequency Online Personal Panel “Life and Work Situations in Times of Corona” (IAB-HOPP). This online survey provides new data to explore the implications of the Covid-19 pandemic on socioeconomic conditions, health, and the employment situation of the working-age population in Germany.

The dataset consists of a random sample of persons that was drawn from the Integrated Employment Biographies (IEB) of the IAB. The IEB includes administrative records of the Federal Employment Agency in Germany covering most persons in dependent employment (but excluding civil servants (Beamte) and the self-employed).

The data cover information on episodes of employment that is subject to social security contributions, of marginal part-time employment, of episodes of receiving unemployment benefits or basic income support, of participation in labour market programs and of registration as a jobseeker. The sample of the survey is limited to persons aged 18 or older on 1 May 2020 with at least one record within the IEB database of the year 2018. Haas and his colleagues (2021) provide a more detailed description of the dataset.

Our analyses rely on data from the first seven survey waves conducted between May 2020 and March 2021. In addition to descriptive analyses, we provide effect plots from a multivariate Hybrid Model.

In our analyses, we use a so-called equivalized household income to make the income of households of different size comparable. To calculate equivalized income, the household’s total income is divided by a weighted household size, which for multi-person households is smaller than the actual household size. Approaches for calculating this weighted household size (e.g. the well-known OECD equivalence scale) typically weight household members of different age differently to reflect the differing needs of adults, youth, and smaller children. As our data do not include detailed information on the age structure of household members, we equivalized household income using the square root scale approach, which divides household income by the square root of the number of people living in the household.

In brief

- Younger adults were more vulnerable to adverse influences of the Covid-19 pandemic on employment and household income than more established workers.

- However, the relevance of these economic influences for their life satisfaction seems to be limited, at least during the early phase of the pandemic.

- What seems to have lowered life satisfaction are Covid-19 incidence rates and being single. Particularly, the lower likelihood of younger individuals to live with a partner might have contributed to their lower life satisfaction throughout the pandemic.

Literature

Beznoska, Martin; Niehues, Judith; Stockhausen, Maximilian (2021): Verteilungsfolgen der Corona-Pandemie. Staatliche Sicherungssysteme und Hilfsmaßnahmen stabilisieren soziales Gefüge, in: Wirtschaftsdienst, Vol. 101. , No. 1, pp. 17-21

Blanchflower, David G. (2021): Is happiness U-shaped everywhere? Age and subjective well-being in 145 countries. Journal of Population Economics 34, pp. 575-624.

Dietrich, Hans; Henseke, Golo; Achatz, Juliane; Anger, Silke Christoph; Bernhard; Patzina, Alexander (2021): Youth unemployment in Germany and the United Kingdom in times of Covid-19. In: IAB-Forum, 04.08.2021.

Grabka, Markus M.; Braband, Carsten; Göbler, Konstantin (2020): Beschäftigte in Minijobs sind VerliererInnen der coronabedingten Rezession, DIW Wochenbericht 45/2020, pp. 841-847.

Haas, Georg-Christoph. et al. (2021): Development of a new COVID-19 panel survey: the IAB high-frequency online personal panel (HOPP). In: Journal of Labour Market Research, Vol. 55.

Kratz, Fabian; Brüderl, Josef (2021): “The Age Trajectory of Happiness.” PsyArXiv Preprint.

Kuhn, Ursina et al (2021): Who is most affected by the Corona crisis? An analysis of changes in stress and well-being in Switzerland. European Societies, 23:sup 1.

Volkert, Marieke et al (2021): Dokumentation und Codebuch für das Hochfrequente Online Personen Panel „Leben und Erwerbstätigkeit in Zeiten von Corona” (IAB-HOPP, Welle 1-7). FDZ-Datenreport 4/2021.

picture: contrastwerkstatt/stock.adobe.com

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20231229.01

Achatz, Juliane; Christoph, Bernhard ; Anger, Silke (2023): Younger and less satisfied? Young workers’ life satisfaction during the Covid-19 pandemic in Germany, In: IAB-Forum 29th of December 2023, https://www.iab-forum.de/en/younger-and-less-satisfied-young-workers-life-satisfaction-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-germany/, Retrieved: 27th of April 2024

Authors:

- Juliane Achatz

- Bernhard Christoph

- Silke Anger

Juliane Achatz is a senior researcher in the research department "Joblessness and Social Inclusion" at the IAB.

Juliane Achatz is a senior researcher in the research department "Joblessness and Social Inclusion" at the IAB. Dr Bernhard Christoph is a senior researcher in the department "Education, Training, and Employment Over the Life Course" at the IAB.

Dr Bernhard Christoph is a senior researcher in the department "Education, Training, and Employment Over the Life Course" at the IAB. Professor Dr Silke Anger is head of the research department “Education, Training, and Employment Over the Life Course” at the IAB.

Professor Dr Silke Anger is head of the research department “Education, Training, and Employment Over the Life Course” at the IAB.