Long-term unemployment in Germany and Europe

- In 2014, more than 12 million people in the EU were long-term unemployed (unemployed for 12 months or longer) – that is, 5 per cent of the economically active population (according to figures from the International Labour Organisation). However there are considerable differences among EU Member States: the long-term unemployment rate ranges from 1.5 per cent in Austria and Sweden and 2.2 per cent in Germany, to 19.5 per cent in Greece.

- In the EU, the number of people who have been out of work for more than a year has doubled since 2007. Today, the long-term unemployed account for roughly half of all unemployed people in the EU. In 2014, 62 per cent of them had been out of work for at least two consecutive years.

- Contrary to the European trend, there was a clear reduction in the number of long-term unemployed in Germany between 2006 and 2011. Since the beginning of the economic and financial crisis, Germany has experienced the biggest drop in the long-term unemployment rate in the EU.

- However, long-term unemployment in Germany is characterized by especially long individual periods of worklessness. Here, nearly a fifth of all unemployed people were unemployed for four years or more. That is much higher than in most other comparable EU countries (Austria, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland).

- Risk factors, such as a lack of or low qualifications, poor language skills, health problems or age are highly correlated with long-term unemployment in all EU countries. However, persons with such barriers find themselves in differing social security systems and are subsequently categorised differently.

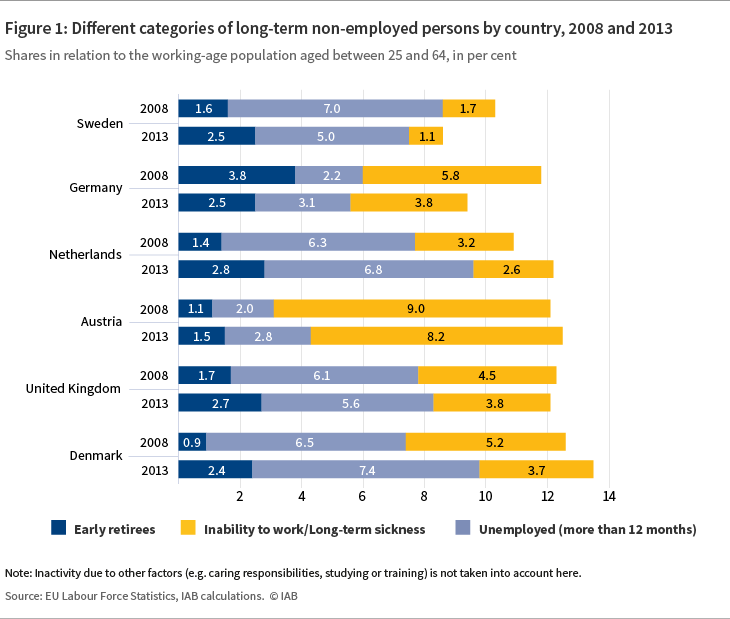

- Due the extremely low threshold for capacity to work in Germany, more people with social and health-related barriers are categorized as long-term unemployed than in other comparable EU-countries, where they may be awarded sickness benefit and therefore not categorised as unemployed (see figure 1).

- International evidence of successful strategies for getting those who are alienated from the labour market back into work is very limited. Studies by the IAB suggest that even people who have been out of work for a long period of time profit from measures that are strongly geared towards direct integration into gainful employment. These strategies include recruitment subsidies or on-the-job training measures. International findings come to similar conclusions. Whilst these results are generally positive, their effects can only make a small impact on the reduction of long-term unemployment as a whole. On the other hand, it also has to be assumed that an economic revival in crisis-hit EU countries will not be sufficient to get all long-term unemployed people back into work. This is why there is a need for effective labour market policies.

Youth unemployment in Germany and Europe

In the EU, roughly 5.1 million young people between the ages of 15 and 24 were without work in 2014. This amounted to 9.2 per cent of all young people; and a full 22.2 per cent of those young people were actively seeking work.

In Germany, the picture is much more favourable. The proportion of unemployed young people in relation to all young people amounted to 3.9 per cent in 2014. Measured against those young people ready for or seeking work, the unemployment rate was 7.7 per cent (see figure 2).

The severe recession of 2008/09 increased youth unemployment in almost all EU-countries; however the extent of the problem varied greatly between countries.

The recession did little to change age-related unemployment risks – in other words, the crisis raised unemployment in all age groups by more or less the same extent. The risk of unemployment is higher for young people than for adults for various reasons – amongst other things because the transition from school or university to working life is not always successful and young people are subject to higher turnover in work.

For a long time, and in contrast to other European countries, the risk of unemployment for young people in Germany had not been much higher than that for adults. In the course of the 2000s however this changed in line with the European pattern: at present, young people in Germany have a roughly 50 per cent higher risk of becoming unemployed than adults. Across the EU as a whole, young people’s risk of unemployment is 250 per cent higher than for EU adults.

However, whilst young people in the EU have a higher risk than adults of becoming unemployed, they nevertheless remain unemployed for a distinctly shorter time than workers over the age of 25. This is also the case in Germany.

In those southern European countries hit by the financial crisis, many unemployed people take a very long time to find a job because of academic over-qualification. This was also the case before the crisis. In general, however, the risk of become unemployed is larger and more long-term for those with low qualifications than for university graduates. This applies to Europe as a whole, including Germany.

On-the-job-training facilitates a more effective transition from education or training into employment and reduces the risk of unemployment. However, Germany’s dual system of vocational training has specific prerequisites that cannot automatically be transferred to other countries (such as countrywide recognized vocational schools, which organize the school part of apprenticeship training; the chambers of trade and commerce or crafts, which supervise the training companies and organise the exams; the social partnership between government, employer and employee organizations in developing the curricula of apprenticeship training or the creation of new apprenticeship training places; or the Federal Employment Services, who support the matching of training applicants and training firms).

Training young persons from southern crisis-hit countries in Germany could make a contribution to transferring the German model of the dual system of vocational education and training to other countries. Moreover this could contribute to strengthening the integration of labour markets in Europe. This is especially supported by schemes such as the European Youth Guarantee and the programme ‘MobiPro-EU’.

However the most important factor for the reduction of youth unemployment in Europe remains stronger economic growth.