22. November 2022 | Digital and ecological transformation

Double-edged sword: How does digitalisation impact on gender inequality in the labour market?

The proportion of tasks that could be performed by computers and computer-controlled machines varies greatly between occupations. To describe this, the term “substitution potential” has become common in this field – regardless of whether the potential for substitution is actually applied in reality. Substitution potential is highest amongst manufacturing occupations and lowest in social- and cultural-service occupations, as shown in an article by Katharina Dengler and Britta Matthes published in December 2018. Since the distribution of the occupations differs between men and women, the substitution potential varies correspondingly.

Women do more jobs that robots are not yet able to perform

On average, men are more likely than women to work in occupations in which the proportion of potentially substitutable tasks is higher. However, this gap has narrowed in recent years. In 2013, for example, women worked in occupations with an average substitution potential of 33 percent. This means that, even then, on average 33 percent of the tasks done by women could be performed by computers or computer-controlled machines. For men, the value in 2013 was 42 percent.

By 2016, the average substitution potential for tasks performed by women had risen by 12 percentage points to 45 percent, slightly more than for men, which increased by 11 percentage points to 53 percent. So, the gender gap narrowed slightly. For 2019, for which the most recent figures are available, the figure was 49 percent for women and 55 percent for men. The gender gap has thus decreased from 9 to 6 percentage points between 2013 and 2019.

Tasks that are predominantly performed by women are becoming substitutable

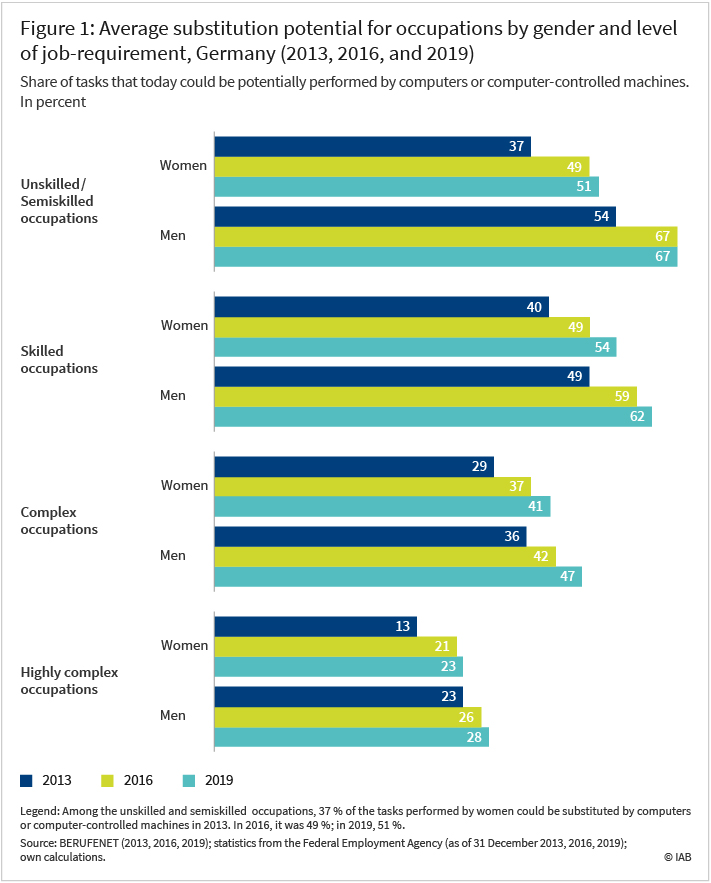

The fact that women are on average less likely to do work that could be performed by computers or computer-controlled machines was and remains true for all requirement levels (see Figure 1):

- In 2019, women in unskilled and semiskilled occupations had an average substitution potential of 51 percent, while men had 67 percent.

- In occupations at skilled level, the respective shares were 54 and 62 percent.

- In complex occupations, the average substitution potential was 41 percent for women and 47 percent for men.

- In highly complex occupations, the figure was 23 percent for women and 28 percent for men.

Particularly notable changes can be observed between 2013 and 2019 within the highly complex occupations: here, the substitution potential increased by 10 percentage points for women and by 5 percentage points for men. In the unskilled/semiskilled, skilled-worker, and complex occupations on the other hand, this increase was only one percentage point higher for women than for men.

One reason for this is that, especially in occupations typically carried out by women, increasingly more technologies can be used that lead to higher substitution potential (read also the IAB Brief Report 4/2018 by Katharina Dengler and Britta Matthes – only available in German). These technologies are, in particular, mobile, collaborative robots, and self-learning computer programmes. The following examples may illustrate possible applications:

- The service-robot “Pepper” can recognise faces and human emotions and support companies, for example, in receiving, informing, and orienting visitors.

- The mobile robot assistant “Care-O-bot 4” can for example be used for pick-up and delivery services in care facilities and offices, for security applications or as an information kiosk

- Robotic-process-automation uses self-learning software bots to perform routine tasks that are typically done by skilled workers.

In the meantime, many administrative and clerical tasks can now be fully automated. These are predominantly performed by women. This includes decision-making procedures, for example for granting loans or checking insurance applications or tax returns (for more on this, see the IAB Brief Report 13/2021 by Katharina Dengler and Britta Matthes – only available in German). This is one of the reasons why the average proportion of substitutable tasks amongst women in the complex occupations is now greater than in the unskilled occupations. This was still different in 2013 (see Figure 1).

In some occupational segments women have a higher substitution potential than men

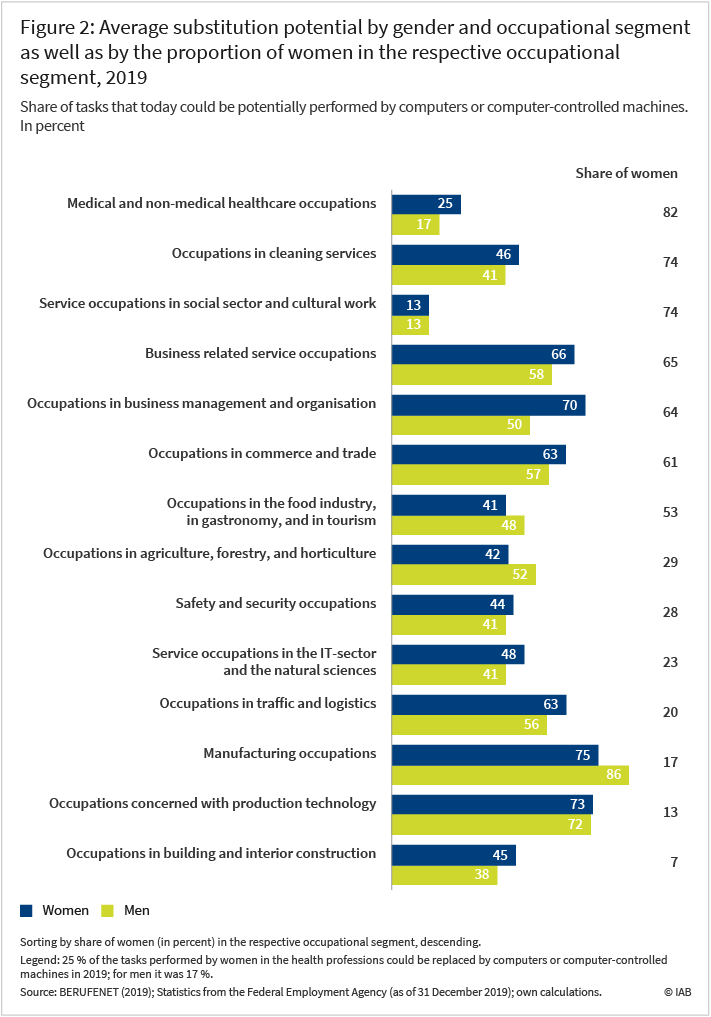

Even if, on average, women are less likely to do substitutable work than men, this by no means does not apply equally to all occupations. Indeed, in some occupational segments, the tasks that women perform have a higher substitution potential than those of men (see Figure 2). Katharina Dengler and Britta Matthes already determined this in an analysis for the year 2016 (only available in German).

For 2019, the largest gender-specific difference can still be identified for the occupations in business management and organisation, where the substitution potential for women is significantly higher than for men (70 versus 50 percent). In this occupational segment, women are disproportionately more likely to work in skilled commercial occupations which have a medium to high substitution potential (e.g. office clerks). In contrast, men work more often as managers, managing directors, plant-, project-, or group leaders, i.e. in occupations with a low substitution potential. Women are therefore potentially more affected by digitalisation than men; partly because the proportion of women in this occupational segment is comparatively high at 64 percent.

On the other hand, within the manufacturing occupations, men work much more frequently in occupations with high substitution potential than women. Here, it amounts to 86 percent for men and 75 percent for women. In the occupational segment of agriculture, forestry, and horticulture, the substitution potential is also significantly higher for men at 52 percent than for women at 42 percent. In these occupational segments, men are more likely to be employed in occupations with a high substitution potential – for example as a process mechanic, foundry mechanic, toolmaker, gardener, or farmer. Women, on the other hand, work more frequently in occupations with medium substitution potential, for example as a media designer, flexographer, industrial and product designer (both manufacturing occupations), horse groom, or florist.

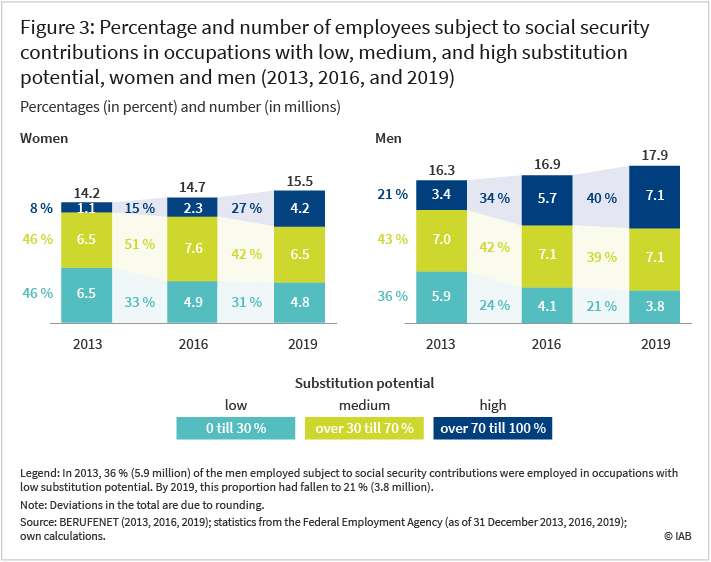

Proportion of women working in occupations with high substitution potential is increasing more rapidly compared to men

Figure 3 shows how the proportion of employees with high, medium, and low substitution potential has developed in recent years for both genders. The substitution potential is considered low if the proportion of tasks that could be performed by computers or computer-controlled machines is no more than 30 percent. A medium substitution potential means that the proportion of substitutable tasks is between 30 and a maximum of 70 percent. In turn, a high potential for substitution means that more than 70 percent of the tasks that arise could be performed by computers or computer-controlled machines.

In 2019, 27 percent of women (4.2 million) and almost 40 percent of men (7.1 million) in employment subject to social security contributions worked in an occupation with high substitution potential. Thus, the percentage of women in employment subject to social security contributions who are affected by a high potential for substitution is still significantly lower than that of men.

However, the increase in substitution potential between 2016 and 2019 was twice as strong amongst women as for men: In 2016, only around 15 percent of women (2.3 million) and 34 percent of men (5.7 million) were employed in occupations with a high level of substitution potential; this proportion increased by 12 percentage points for women by 2019, but only by 6 percentage points for men. Men are more likely to work in the highly substitutable manufacturing production-technology occupations. In recent years, however, tasks within occupations which are typically carried out by women have increasingly become substitutable by digital technologies.

Conclusion

It is true that, on average, in Germany women perform substitutable tasks less frequently than men across all occupational requirement levels. However, it cannot be deduced from this that the digital transformation would automatically reduce the existing gender-specific inequalities in the labour market. On the one hand, there are occupations in which women are more affected by digitalisation than men. On the other, substitution potential only shows the technological potential – and not necessarily the practised reality of the digital transformation.

40 percent of men work in occupations with high substitution potential, but only 27 percent of women. The potentially greater impact on men could result in a greater decline in male than in female employment. The decision as to whether and when this potential will be realised is ultimately made by people. Multivariate analyses show that for 2013, in occupations with higher substitution potential, employment grew less rapidly between 2013 and 2016 – for both genders, but especially for men.

However, the digital transformation encompasses many more aspects than just the question of the substitutability of occupational tasks. This is another reason why it has the potential to break up traditional gender relations in the labour market. Many technical aids are now available that make it easier for women to practise jobs that were previously reserved for men. For example, lower physical strength can be compensated for by using intelligent, adaptable exoskeletons.

The task profiles of the professions have also changed: in the course of digitalisation, the boundaries between classic male and female professions are increasingly becoming blurred. For example, social aspects could play a stronger role in the engineering professions. Conversely, digital technologies are increasingly being used in occupations in which women are still predominantly employed. In the future, this could also make such occupations more attractive for men.

Technology still tends to have a male connotation: According to the results of a 2020 survey by the Initiative D21 on the “Digital Gender Gap”, those surveyed are still more likely to attribute technical skills to men, whilst women are on average seen as more technology-averse. In addition, men are more likely to develop technologies and women are more likely to use them, to strongly simplify the findings of a 2019 study on “Digital Skills” by Nina Czernich and others. This could prove to be a significant career barrier for women.

Further, it would be worth discussing how to create greater gender equality in the labour market. Could more participation by women in the development of digital technologies lead to greater gender equality? Would this be possible if more women took up STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math.) professions. What contribution could a more gender-equitable division of household- and care-work make? The new technological possibilities thus merely create the preconditions and the occasion for breaking up traditional gender relations – it will by no means happen automatically.

Literature

Burkert, Carola; Dengler, Katharina; Matthes, Britta (2022): Die Folgen der Digitalisierung für die Geschlechterungleichheit auf dem Arbeitsmarkt: Substituierbarkeitspotenziale und die Beschäftigungsentwicklung bei Frauen und Männern. In: Sozialer Fortschritt, Vol. 71, No. 1, pp. 3-27.

Czernich, Nina; Fackler, Thomas; Falck, Oliver; Schüller, Simone; Wichert, Sebastian; Keveloh, Kristin; Vijayakuma, Ramanujam Macharla (2019): Digitale Kompetenzen – Ist die deutsche Industrie bereit für die Zukunft? Ifo Institut und LinkedIn.

Dengler, Katharina; Matthes, Britta (2018): The impacts of digital transformation on the labour market. Substitution potentials of occupations in Germany. In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 137, No December, pp. 304-316.

Dengler, Katharina; Matthes, Britta (2021): Folgen des technologischen Wandels für den Arbeitsmarkt: Auch komplexere Tätigkeiten könnten zunehmend automatisiert werden, IAB- Brief Report No. 13.

Dengler, Katharina; Matthes, Britta (2020): Substituierbarkeitspotenziale von Berufen und die möglichen Folgen für die Gleichstellung auf dem Arbeitsmarkt. Expertise für den Dritten Gleichstellungsbericht der Bundesregierung.

Dengler, Katharina; Matthes, Britta (2018): Substituierbarkeitspotenziale von Berufen: Wenige Berufsbilder halten mit der Digitalisierung Schritt, IAB-Brief Report No. 4.

Dengler, Katharina; Matthes, Britta (2016): Auswirkungen der Digitalisierung auf die Arbeitswelt: Substituierbarkeitspotenziale nach Geschlecht. Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, Aktueller Bericht No. 24.

Initiative D21 e. V. (2020): Digital Gender Gap. Lagebild zu Gender(un)gleichheiten in der digitalisierten Welt.

In brief

- On average in Germany, women are less likely than men to do work that could potentially be done by computers and computer-controlled machines.

- However, this is not the case in all occupations. A look at the substitution potential for women and men differentiated by occupational segment shows that there are also occupational segments in which women have a higher substitution potential.

- As a result of technological progress, occupations that are mainly done by women are becoming increasingly substitutable. It is true that the proportion of women in employment subject to social security contributions who are affected by a high potential for substitution is significantly lower than that of men. However, the increase between 2016 and 2019 was twice as high for women.

- Although women, on average, perform substitutable tasks less frequently than men across all requirement levels, it cannot be concluded from this that the digital transformation would automatically reduce existing gender-specific inequalities in the labor market. This remains primarily a policy task.

DOI: 10.48720/IAB.FOO.20221122.01

Burkert, Carola; Grienberger, Katharina ; Matthes, Britta (2022): Double-edged sword: How does digitalisation impact on gender inequality in the labour market?, In: IAB-Forum 22nd of November 2022, https://www.iab-forum.de/en/double-edged-sword-how-does-digitalisation-impact-on-gender-inequality-in-the-labour-market/, Retrieved: 28th of April 2024

Authors:

- Carola Burkert

- Katharina Grienberger

- Britta Matthes

Dr Carola Burkert is senior researcher in the Regional Research Network at the IAB.

Dr Carola Burkert is senior researcher in the Regional Research Network at the IAB.  Dr Katharina Grienberger is senior reseracher in the research group "Occcupations in the Transformation" at the IAB.

Dr Katharina Grienberger is senior reseracher in the research group "Occcupations in the Transformation" at the IAB.  Dr Britta Matthes is head of the research group "Occupations in the Transformation" at the IAB.

Dr Britta Matthes is head of the research group "Occupations in the Transformation" at the IAB.