25. October 2023 | Wages and Employment

How men and women differ when searching for a job: application behaviour can explain half of the residual earnings gap

In recent decades, female labour force participation has been increasing significantly and the gender pay-gap has narrowed as the Federal Statistical Office shows in a report from 2023. However, using data from 2010 to 2016, Benjamin Lochner and Christian Merkl (2022) show that newly hired women in Germany earn 23 percent less than men. Comparing women and men who work in similar occupations and have similar characteristics, such as age or formal education, the residual earnings gap is 14 to 15 percent.

The common approach to measuring differences in earnings between women and men ignores, however, certain factors that precede the actual hiring (see Infobox). In order to fill a position, two key stages take place: first, applicants have to apply for a specific job. Second, firms then select a suitable candidate from the pool of applicants. Both stages can potentially be the source of starting-wage inequalities between women and men. On the one hand, women may apply less frequently than men for certain, potentially high-paying jobs. As a result, there would be more men in the pool of applicants and women would thus have a lower than average chance of being hired for high-wage jobs. This would lower women’s average earnings overall as a result. On the other hand, it is possible that despite comparable applications from both genders for a vacancy, certain employers hire women less frequently than men for certain jobs. The first stage in particular, i.e. gender-specific application behaviour, can be driven by the fact that certain jobs have different characteristics and requirements such as different working conditions. The following article focuses on the application behaviour of newly hired women and men and its implications for the earnings gap.

Women are less likely to apply to high-wage firms

For a better understanding of the first stage of the hiring process, Benjamin Lochner and Christian Merkl (2022) analysed the application behaviour at firms with different firm-specific wage premiums. This “wage premium” measures whether firms pay more or less on average than other firms when differences in education, age and composition of the workforce are taken into account.

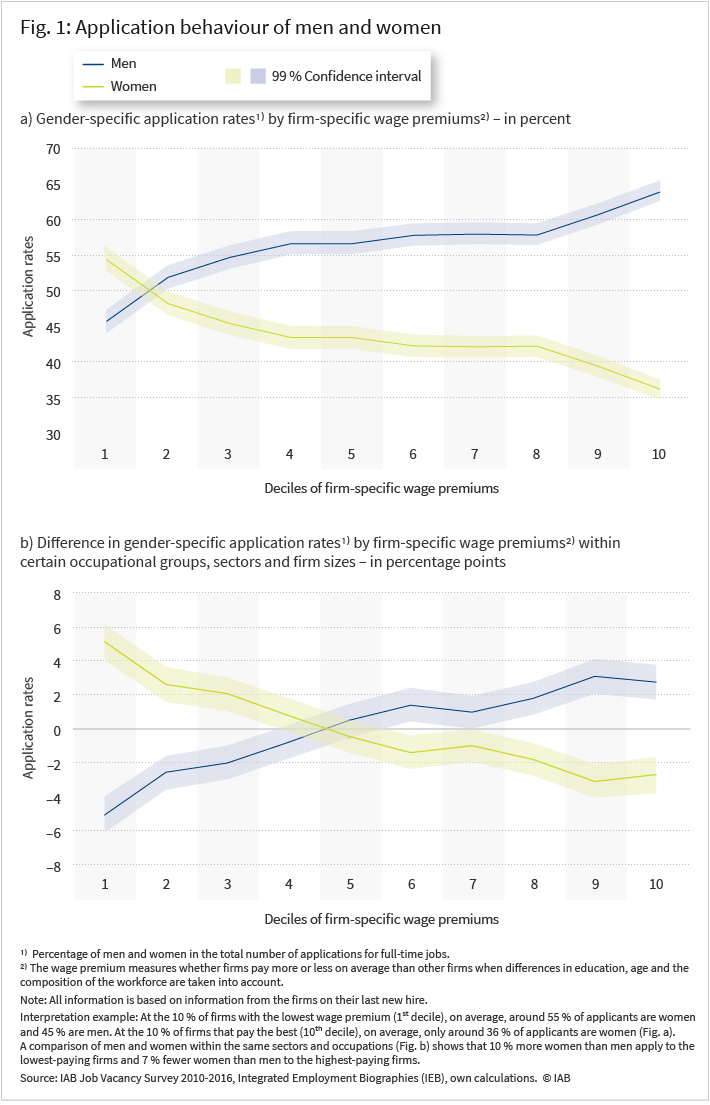

Figure 1 sorts hiring firms by their wage premiums and shows their corresponding gender-specific application rates for full-time jobs. It becomes clear that women are less likely to apply to firms with higher premiums and more likely to apply to firms with lower premiums. In the 10 percent of firms with the lowest wage premiums, on average 55 percent of applicants are women and 45 percent are men. By contrast, in the 10 percent of firms that pay the best, the average proportion of women in the application pool is only around 36 percent.

A possible explanation for this pattern is that women work more often than men in poorly-paid occupations and sectors. However, it is important to emphasise that this pattern persists even when comparing the application behaviour of workers looking for jobs in the same industry, occupation and in similarly sized firms. Figure 2 shows the difference in gender-specific application rates within certain occupational groups, economic sectors and firm sizes. It becomes clear that the differences are largely reduced in this regard, especially in firms with higher wage premiums. The choice of industry, firm size and occupation can therefore explain part of gender-specific application behaviour, with the choice of occupation being the dominant factor. Nevertheless, major differences remain. If one compares the application rates of both genders for the same target occupations and -sectors, the proportion of female applicants in the firms with the lowest wage premiums is about 10 percentage points higher and the proportion of male applicants in the firms with the highest wage premiums is 7 percentage points higher.

No evidence of selection differences at the recruitment stage

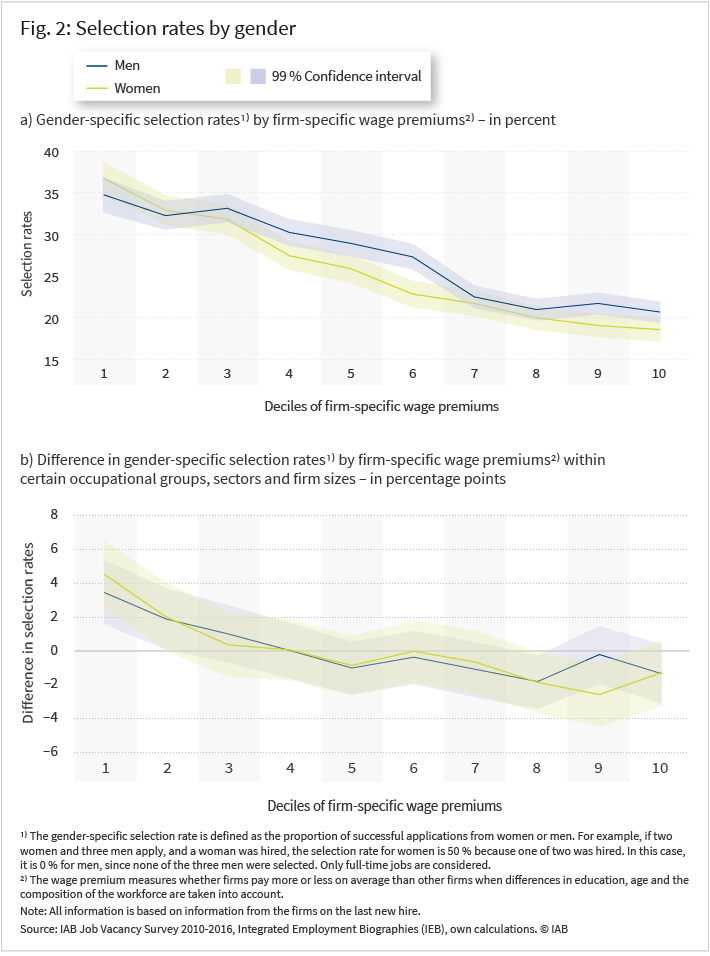

Figure 2a shows the gender-specific selection probabilities for firms with different firm-specific wage premiums. In firms with higher wage premiums, the selection probability is lower for both women and men. This is partly driven by firm size: larger firms have higher wage premiums on average and consequently receive more applications.

However, it is also clear that the difference between the likelihood of men and women being selected is relatively small (compared to the gender differences in application rates). Figure 2b shows that the differences in the selection rates between firms disappear if one only compares recruitments in firms of comparable size, in the same economic sector and in the same occupation. So, if women and men apply for the same job at high-wage firms of comparable size and industry, their probability of getting the job is ultimately the same.

The observation that women work more rarely in high-wage firms is therefore mainly due to workers’ application behaviour and not due to firms’ hiring behaviour. The application behaviour is, however, also related to employer-side flexibility requirements, which is shown below.

Gender-specific application behaviour can explain a large part of the earnings gap

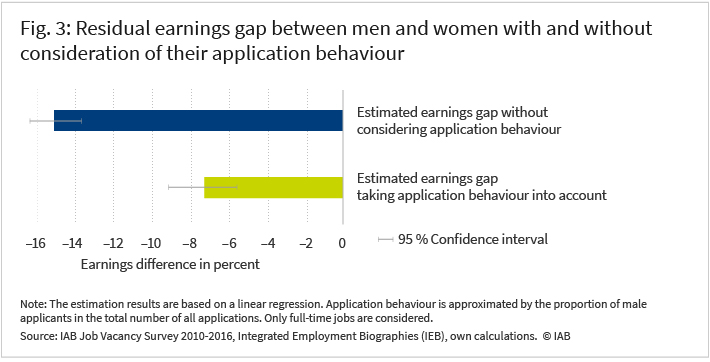

Applicant-pool information from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey allows application behaviour to be taken into account when calculating the difference in earnings between men and women. According to Benjamin Lochner and Christian Merkl (2022), the adjusted earnings gap for newly hired employees in full-time jobs is around 14 to 15 percent. When the application behaviour is taken into account, the adjusted earnings gap falls to around 7 percent (see Figure 3). Gender-specific application behaviour, approximated with the proportion of male applicants, can therefore explain a considerable part of the earnings gap.

Well-paid jobs with high flexibility requirements are often unattractive for women

Since gender-specific application behaviour is relevant to the earnings gap, the question arises as to whether there are certain job-characteristics which are particularly unattractive for women. The IAB Job Vacancy Survey provides information on the characteristics of firm vacancies which go beyond the simple job title. Attributes which reflect employers’ flexibility-requirements appear to be particularly important in this context. For example, the proportion of male applicants is higher when the number of weekly working hours or the use of overtime increases.

Gender differences also become particularly clear when looking at jobs where working hours change frequently or where a high degree of local mobility is expected. For example, if a job is often associated with mobility, the proportion of male applications is 65 percent.

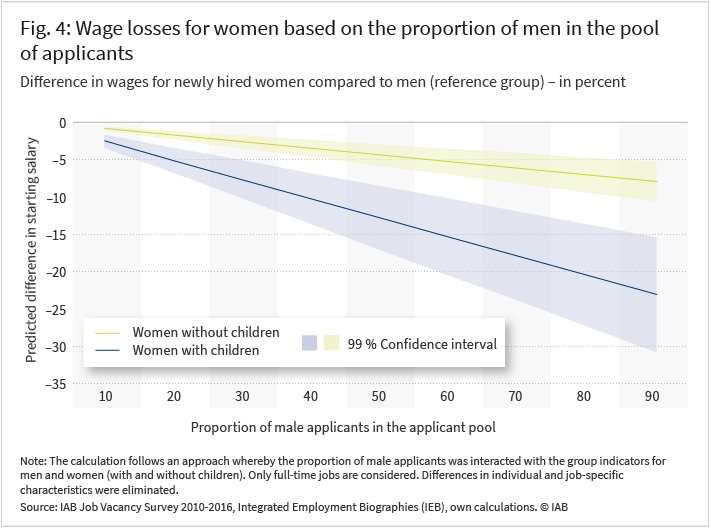

With regard to flexibility requirements, application behaviour presumably also depends on whether children live in the household. However, the data does not allow for a distinction to be made between women with and without children in the application pool. Below, however, we show that hired women with children experience greater earnings-losses than women without children in comparison to men.

Earnings-differences according to different job-flexibility requirements

These application- and hiring patterns are consistent with the hypotheses of Claudia Goldin (2014) as well as Benjamin Lochner and Christian Merkl (2022) that jobs can have different employer-side flexibility requirements. For jobs with high requirements, applicants only become attractive to the firm if they are able to provide this flexibility – for example, with medical doctors who have to be available for night shifts or for employees of an international firm who are expected to travel extensively. Such jobs are generally better paid, but can be harder for people with caring-responsibilities to take on. For example, in the pool of applications for jobs that involve frequent business trips and changing workplaces, only around 35 percent are women, on average. This would also explain part of the earnings gap.

As already explained, there is a clear positive correlation between the proportion of male applicants and the flexibility requirements considered. For this reason, the proportion of men in the pool of applicants is used as an approximation for the level of flexibility requirements. It is noticeable that the difference in earnings between women and men is particularly high in jobs for which, on average, many men apply. For jobs with 90 percent male applicants, women without children earn on average around 8 percent less than men. For women with children, the difference is more than 20 percent. One possible reason is the systematic discrimination against women (with children) in jobs with a high proportion of men in the applicant pool. However, the fact that the selection probability is similar for men and women at high-paying firms speaks against this (see Figure 2). Another reason could be the hypothesis described above: Employees who are on average more flexible are better paid. If women are able to meet the flexibility requirements to a lesser extent due to the larger average amount of care work (including looking after children), this would partly explain the lower earnings of women in these jobs.

Conclusion

This report shows that there are large differences in job-application behaviour between women and men and that these differences can explain a large part of the adjusted earnings gap. Employer-side flexibility-requirements in particular seem to play an important role here. Measures such as the expansion of government-provided childcare, better opportunities for working from home and firms’ reconsideration of which flexibility requirements are necessary, as well as a more equal division of care work between men and women in the household could help to reduce the earnings gap driven by gender-specific application behaviour.

In Brief

- Firm data from 2010 to 2016 show that the application rate from women – i.e., their share in the pool of applicants for a job – is more than 25 percentage points lower than that from men in high-wage firms.

- On average, newly hired women earn 23 percent less than men. Comparing women and men who do the same job and have many similarities, such as age, the residual earnings difference is 14 to 15 percent.

- If the gender-specific application behaviour is included in the analysis of earnings differences, the adjusted earnings gap is reduced by more than half.

- High demands for flexibility from employers are often associated with lower application rates from women. For example, in the pool of applications for jobs that involve frequent business trips and changing workplaces, only around 35 percent are women, on average.

Data Sources: The IAB Job Vacancy Survey and Administrative Individual Data

This report is based on two data sources that were linked. The first is the IAB Job Vacancy Survey (Mario Bossler et al. 2020), a representative firm survey that the IAB has been conducting since 1989. Information on the overall economic need for labour and on the company recruitment process is collected. Firms are also asked about the last successful recruitment process. Detailed information about the person hired, the specified characteristics of the vacancy and the search process are collected. Information is also included on how many applications for a specific position came from men and women. The second data source is individual data on the people hired (Integrated Employment Biographies, IAB, 2020). This data originally comes from the registration procedure for health-, pension- and unemployment-insurance and is processed by the IAB. Above all, the individual data shows where and for how long someone was employed.

A deterministic matching algorithm is used to identify newly employed individuals from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey in the individual data (for methodological details see Benjamin Lochner 2019). The algorithm uses overlapping information that exists in both data sources. The novel combination of survey and individual data makes it possible to observe important dimensions such as the characteristics of the hiring firm, workers who are hired and the hiring process. This report is based on data from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey from 2010-2016 (more recent data are not yet available). For this period, the combined dataset contains information on 21,694 new hires (Benjamin Lochner 2023).

Literature

- Firm data from 2010 to 2016 show that the application rate from women – i.e., their share in the pool of applicants for a job – is more than 25 percentage points lower than that from men in high-wage firms.

- On average, newly hired women earn 23 percent less than men. Comparing women and men who do the same job and have many similarities, such as age, the residual earnings difference is 14 to 15 percent.

- If the gender-specific application behaviour is included in the analysis of earnings differences, the adjusted earnings gap is reduced by more than half.

- High demands for flexibility from employers are often associated with lower application rates from women. For example, in the pool of applications for jobs that involve frequent business trips and changing workplaces, only around 35 percent are women, on average.

This report is based on two data sources that were linked. The first is the IAB Job Vacancy Survey (Mario Bossler et al. 2020), a representative firm survey that the IAB has been conducting since 1989. Information on the overall economic need for labour and on the company recruitment process is collected. Firms are also asked about the last successful recruitment process. Detailed information about the person hired, the specified characteristics of the vacancy and the search process are collected. Information is also included on how many applications for a specific position came from men and women. The second data source is individual data on the people hired (Integrated Employment Biographies, IAB, 2020). This data originally comes from the registration procedure for health-, pension- and unemployment-insurance and is processed by the IAB. Above all, the individual data shows where and for how long someone was employed.

A deterministic matching algorithm is used to identify newly employed individuals from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey in the individual data (for methodological details see Benjamin Lochner 2019). The algorithm uses overlapping information that exists in both data sources. The novel combination of survey and individual data makes it possible to observe important dimensions such as the characteristics of the hiring firm, workers who are hired and the hiring process. This report is based on data from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey from 2010-2016 (more recent data are not yet available). For this period, the combined dataset contains information on 21,694 new hires (Benjamin Lochner 2023).

Literature

Bossler, Mario; Gürtzgen, Nicole; Kubis, Alexander; Küfner, Benjamin; Lochner, Benjamin (2020): The IAB Job Vacancy Survey: Design and Research Potential, Journal for Labour Market Research, Vol. 54, No.1.

Federal Statistical Office (2023): Unadjusted Gender Pay Gap (GPG) by territory, Access 2023, March 28.

Goldin, Claudia (2014): A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter, American Economic Review, Vol. 104, pp. 1091–1119.

IAB (2020): IAB Integrierte Erwerbsbiografien (IEB). V15.00.00-201912, Nürnberg 2020.

Lochner, Benjamin (2023): IABSE-ADIAB – IAB Job Vacancy Survey Data Linked to Administrative Data, Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, online first, pp. 1–7.

Lochner, Benjamin (2019): A simple algorithm to link „last hires” from the Job Vacancy Survey to administrative records, FDZ-Methodenreport No. 6(en), Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, Nürnberg.

Lochner, Benjamin; Merkl, Christian (2022): Gender-Specific Application Behavior, Matching, and the Residual Gender Earnings Gap, IAB-Discussion Paper No. 22.

DOI: IAB.FOO.20231025.01

Lochner, Benjamin; Merkl, Christian (2023): How men and women differ when searching for a job: application behaviour can explain half of the residual earnings gap, In: IAB-Forum 25th of October 2023, https://www.iab-forum.de/en/how-men-and-women-differ-when-searching-for-a-job-application-behaviour-can-explain-half-of-the-residual-earnings-gap/, Retrieved: 29th of April 2024

Authors:

- Benjamin Lochner

- Christian Merkl

Dr Benjamin Lochner is a senior researcher in the research department forecast and macroeconomic analysis at the IAB.

Dr Benjamin Lochner is a senior researcher in the research department forecast and macroeconomic analysis at the IAB.  Professor Dr Christian Merkl is a research fellow at Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit GmbH (IZA) and the Chair of Macroeconomics at FAU.

Professor Dr Christian Merkl is a research fellow at Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit GmbH (IZA) and the Chair of Macroeconomics at FAU.