1. December 2017 | International Labour Markets

The German Employment Performance in an International Context

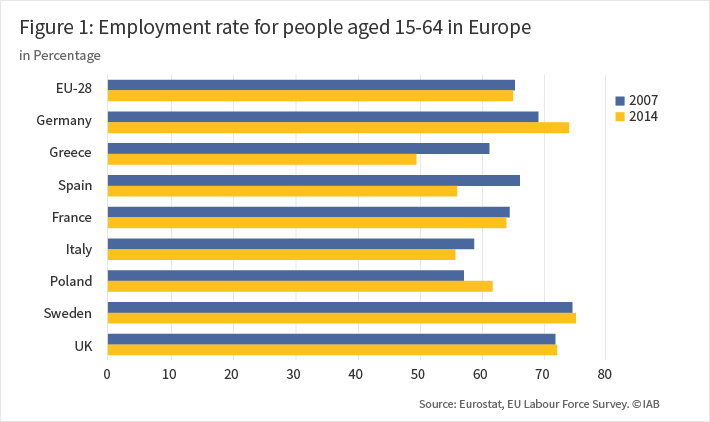

Figure 1 gives an impression of how the financial crisis and the subsequent European debt crisis affected the labour markets in Germany and other European countries. It shows the employment rates in 2007, before the onset of the financial crisis, and for 2014, when the crisis in Southern Europe had reached or just passed its peak. In the EU-28, the 2014 rate is 64.8 percent, barely lower than in 2007 (65.2%). Thus, if you look at the EU member states together, any major labour market impacts arising from the crisis are apparently unobservable. Here, almost two thirds of the working population are still in employment. The rest are either unemployed or inactive for other reasons (e.g. they are in training, unable to work due to sickness, or performing caring responsibilities).

Heterogeneous labour-market developments in Europe

If, however, you look at individual countries, you get a very mixed picture. Figure 1 shows the six largest EU countries plus Sweden, and Greece as the most affected crisis country. Spain and Greece, two southern European countries hit hard by the crisis, are suffering from drastic slumps in employment – particularly in Greece, where the employment rate fell by more than ten percentage points to below 50 percent. In Germany, by contrast, the rate has risen to almost 74 percent, reaching a level that is only slightly exceeded by one other country in the EU: Sweden (75 %). Of note is also the significant positive trend in Poland, the largest Eastern European country, which started from a lower level of employment.

Since 2014, employment growth has continued in Germany, but also in the EU-28 as a whole. This also applies to Greece and Spain, albeit on a modest level, and employment rates in these two countries are still far below the pre-crisis level.

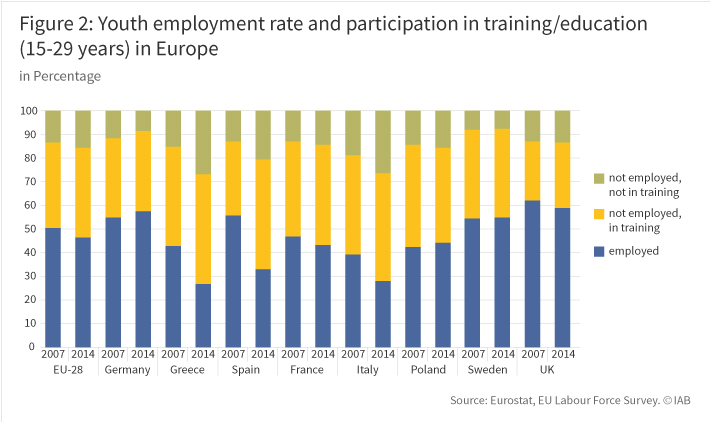

In many countries, young people were particularly impacted by the crisis as a study by Hans Dietrich from 2013 shows. The term ‘youth’ encompasses a relatively wide age range from 15 to 29 years, because individuals’ transitions from education to employment tend to happen later as more young people go on to higher and further education. For this age group, the data for Germany show a high level of employment (57.8 %) in 2014 – only in the United Kingdom is it a little higher with 59.2 percent. This is contrasted by a sharp decline in the crisis countries already mentioned, but also in Italy. In those countries, the proportion of the adolescents who were neither in training nor in gainful employment (i.e. either unemployed or inactive and thus largely cut off from the labour market) increased (see upper part of Figure 2). Their share in these countries was over 20 percent in 2014, compared with only 7.8 percent in Germany. Since 2014, prospects for young people in Southern Europe have changed slightly for the better; but youth non-employment remains one of the most urgent problems in these countries.

All in all, the data shows the exceptionally favourable employment- and labour-market trends in Germany since 2007. But even though the problem of youth unemployment is of a different magnitude than in many other European countries, everything must also be done in Germany to ensure the start of working life runs as smoothly as possible for young people. In particular because the evidence shows that early unemployment permanently constrains further employment trajectories over the long term as a study by Achim Schmillen and Matthias Umkehrer from 2014 shows.

Improvements to German labour-market mechanisms

Evidence such as that presented in Sabine Klinger’s and Enzo Weber’s 2016 study shows that the upswing in the German labour market was accompanied by permanent structural changes. Thus, the upswing was strengthened through an improved functioning of the labour market , such as more efficient matching processes following the comprehensive Hartz reforms) – not simply through growth-fuelled higher demand for labour or through reduced labour costs. Economic growth since 2005 has on average been only moderate. An export-driven boom driven by Germany’s price competitiveness in the global economy can therefore not be attributed as the most important cause of the improvement in the employment rate. In fact, labour supply and search intensity increased, despite weak wage developments.

The places in which German export has been particularly successful since the middle of the last decade have been in emerging markets such as China. Above all, capital goods have been in demand here, for whose production Germany had the right industrial structure. However, with the transition of the Chinese growth model to services and consumption, Germany cannot simply rely on these trade trends continuing. The need to evolve is also important given that a strengthening of investment activity in Germany now increasingly depends on strategies beyond exceptional export dynamics.

The financial crisis has put Europe to the test

Clearly, asymmetric economic developments in the eurozone played a role in the emergence of the European debt crisis, even though explanations which point to a German wage-dumping policy are too narrow. A monetary union, in which there is no exchange-rate mechanism and there are no national monetary policies, relies on mechanisms to balance divergent economic developments. For this purpose, the introduction of a European unemployment insurance has been discussed, which could in particular support countries who are suffering from low employment through insurance benefits to the unemployed. This proposal is challenged by the fact that national unemployment insurance schemes have been designed and have evolved very differently, which calls into question the appropriateness of a standardised supra-national solution. Enzo Weber argues in his IAB-Forum article “European unemployment insurance: finding the golden mean” that the desired equalizing and stabilization effects could also be achieved through a common EU fund financed through taxation, without requiring an intervention into the mature social security systems of the Member States.

Immigration to Germany has risen

Asymmetric economic developments in Europe have fuelled a strong increase in immigration to Germany. In addition to southern European countries, these increased levels of migration stemmed in particular from Eastern European countries, especially after the lifting of free-movement restrictions. As a result of military conflicts in the Near and Middle East and in Africa, a substantial increase in forced migration has added to the numbers in recent years. By contrast, (employment-oriented) immigration from third countries, which will be important in the medium term, remains low as shown in a study by Johann Fuchs et al. from 2016.

Authors:

- Thomas Rhein

- Enzo Weber

Since 1991 Thomas Rhein has been working as a researcher at the IAB.

Since 1991 Thomas Rhein has been working as a researcher at the IAB.  Professor Enzo Weber is Head of the Research Department "Forecasts and Structural Analyses" at the IAB. He develops current policy proposals for labour market and economic challenges and advises national and international governments.

Professor Enzo Weber is Head of the Research Department "Forecasts and Structural Analyses" at the IAB. He develops current policy proposals for labour market and economic challenges and advises national and international governments.